A digital gate open to heritage

The Sanctuary of Estíbaliz

Guided tours

Introduction

The sanctuary of Estíbaliz, located just ten kilometres away from Vitoria-Gasteiz, represents one of the most emblematic places with the longest tradition in the whole Álava. Despite the fact that the Virgin of Estíbaliz has officially been the patron saint of Álava since 1941, her devotion is traceable since the Middle Ages. Throughout its history, the enclave has had different uses and functions: it has been a tenement with a fortress that today no longer exists, it was conceived as a monastery, it had a hospital for pilgrims and travellers of the Way of Saint James, it was a hermitage of great devotion and, in its years of decline, back in the 19th century, it became an agricultural warehouse and private house of a resident of the area. Despite all the vicissitudes of time, the sanctuary of Estíbaliz continues being a reference site for all the alavaise people and one of the Romanesque jewels of the Basque Country.

The amends of Estíbaliz

Tradition has it that the King of Pamplona, Sancho Garcés III the Great, granted a privilege to the alavaise people so that they could resolve their differences and issues on the 1st day of May on the sanctuary of Estíbaliz. At dawn, the alavaise people that had a score to settle went to the church to hear a mass in which the priest urged them to resolve their conflicts peacefully. If they did not reach an agreement, the contenders went outside, where a duel took place. The first to shed a drop of blood lost the fight and the dispute. This tradition, heir of the so-called “judgments of God” or ordeals, has not been confirmed in written documents to date and is considered a literary creation that even had its theatrical version. Still, it is widely popular today and all the alavaise people go to the sanctuary every 1st of May, not to make amends, but rather to enjoy the traditional festival of Estíbaliz.

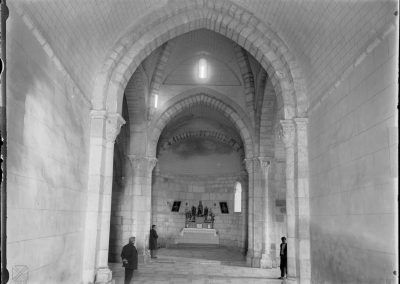

Old photographs

After a difficult 19th century, the century ended with the need of revitalizing the sanctuary and restoring not only the cult, but also the splendour to its Romanesque church. It was a period of continuous restorations that the photographs reveal, in which we see how the historical elements added to the church disappear, such as the pilgrim hospital attached to the south wall, and some neo-Romanesque additions start to appear, such as the sacristy, the gallery that connects the monastery with the church or the last body of the bell gable, knocked down during a hurricane in 1941. It is striking to verify how, before the restorations, the hill of Estíbaliz was an abandoned area where only the church existed and how, during the 20th century, all the elements of the current complex were added, including many of the trees that surround the sanctuary.

The basilica of Santa María de Estíbaliz

Facades

Despite the intense restorations that the temple went throughout the 20th century, it still preserves most of the medieval elements. For example, the west facade, current access to the church, was moved and rebuilt again six metres away from its original place to expand the church space during the 1927 restoration, but the materials that it is composed of and the design were mainly maintained. We can observe the sobriety that this facade shows and that contrasts with the decorative profusion of the south facade, called Puerta Speciosa.

The «portada Speciosa»

This facade is named after an ancient psalm that was sung to the Virgin before entering the interior of the church during the pilgrimages. The sculptural quality of the workshops that carried out this facade is astonishing. The column shafts are composed of a basket pattern and a reticle with flowers and dots, and on the capitals we see different vegetable themes among which some figurative element appears. On the doorjambs, somewhat damaged by the passing of time, a series of vegetable rinceaux can still be guessed, which, in the case of the right doorjamb, accommodates a series of characters on uncomfortable and impossible positions. At the top of both doorjambs two characters stand out: a possible prophet, sometimes identified as Saint John the Baptist, and a Christ Pantocrator or Christ of the Last Judgement who is judging humanity after his Second Coming.

There are a number of elements on the main facade of Estíbaliz that, given its location and style, reveal that they have been placed there at a later date. Among the most interesting remains we find an Annunciation, with the angel Gabriel and the Virgin placed on a wavy surface between columns. Behind this scene, we can see various incongruous elements on the corner, like a scene with two women raising their skirts, a capital with acanthus leaves and a beautiful representation of a centaur throwing an arrow and piercing a harpy with it. On the other side of the facade, on the corner, there is also an Atlas holding a capital with great effort.

Estíbaliz preserves a truly interesting set of corbels, although some of them are difficult to interpret due to the erosion. Over the Puerta Speciosa we find a line of corbels with representations of human faces, geometrical elements and a wolf. Most notable on this set is a hideous image with sharp teeth that shares the corbel with a male head with a moustache. The corbel that holds one of the small columns of the bell gable deserves special mention, in which we can see a round head on which an enormous serrated smile stands out. On the apses, most of the corbels are plain, except for the central one, in which we see a series of representations of animals, both fantastic and real, among which a capital with the figure of a siren used as a bracket stands out.

The interior of the temple

Capitals of the interior

We find two types of capitals inside: vegetable and figurative. The vegetable-themed capitals are gathered in the transept, in the area of the nave. Two of them have a similar design based on leaves and fleurs de lis on the corners, while the other two offer filigrees of great sculptural quality, with faces and animals hidden among the foliage.

In the area of the presbytery we find four more capitals, this time with a figurative theme. In the first one, the Original Sin is narrated to us, the moment in which Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit and, in doing so, feel ashamed of their nakedness. From above, God the Father discovers that they have broken his command. The next capital shows the expulsion from Paradise and how an angel with a sword points at the exit door and pushes them to force them to abandon the place. On another capital we are shown, in addition, other sins committed by humanity, such as the sin of greed, represented by a man from whose neck hangs a bag of coins who is being tortured by a demon. On its side we see the punishment to the female lust, represented by a naked woman from whose breasts hang a frog and a snake.

The last capital is reserved for redemption and the possibility of salvation, carried out by the Virgin Mary at the moment of the Annunciation. On the scene, the angel and the Virgin appear, over whom the dove of the Holy Spirit approaches, holding a cartouche that reads: AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA.

Baptismal font

The baptismal font is a copy of the 12th-13th centuries, in whose bowl we can contemplate, among a series of arches, four masculine faces well differentiated from each other and a set of animals among which we find lions, bears or eagles. The bowl is hold by four small columns with damaged capitals that end in a series of leaves that cover the lower side of the font.

The Virgin of Estíbaliz

In the middle of the apse of the church, in a preeminent position, we find the carving of the Virgin of Estíbaliz. It is a Virgin with the child, a type known as “Andramari”, whose origin dates from the late 12th or early 13th century. Just like the building, it has gone through countless vicissitudes due to its age. In the 19th century it was partially destroyed and ended up in a very bad state of conservation, which forced the residents of Villafranca to act urgently. With the spirit of renewal that arrived in the early 20th century, the carving was intensely restored with a new face, hand and child. She is currently the patron saint of Álava and one of the religious images that awakens greater devotion in the people of Álava.

Créditos fotográficos:

De las fotografías actuales: © Alava Medieval / Erdi Aroko Araba

De las fotografías antiguas: Archivo Municipal de Vitoria-Gasteiz.