A digital gate open to heritage

Introduction

In the small town of Alaitza, we find one of the most astonishing churches in the Basque Country. What we can see from the outside is a simple Romanesque temple with a semicircular east end with two naves and a porch. However, the true wealth is found inside, as it contains an extensive and rich programme of medieval painting that has become an enigma hard to solve. The documentary news about the origins of the town is late and it was in 1257 when we first find it by the name of “Halayça”. The information is multiplied from the 14th century, a key stage in which we will see that a series of important renovations are made in the church.

The discovery of the paintings

In the early eighties, the parish priest of the town, Juan José Lecuona, took a ladder and, with a knife in his hand, started to scratch the white layers of lime that covered the semi-dome of the apse. To his surprise, the outline of a horse appeared on a location that hinted at the existence of a large painting. The restoration of the temple began soon, bringing to light the collection that can be seen today. The lost parts (and the subsequent destructions, such as the opening of a skylight made in the 19th century) were finished with a more orange paint that allowed distinguishing the intervention and, thus, visually completing the decorative development.

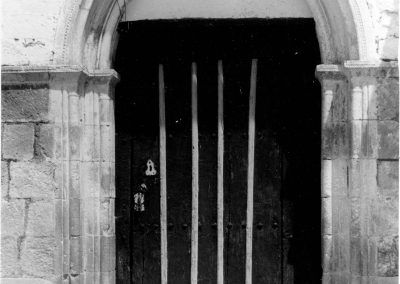

The old photographs of Alaitza show us the important changes suffered by the church in the last decades. We see how the altarpiece took up part of the east end and also the large skylight that was opened on the apse to light up the altar. All of them show us the white walls, whitewashed, still without trace of the images that will appear some time later. Likewise, on the exterior, we can see the parish house that was attached to the south wall, demolished in the eighties.

The church of Our Lady of the Assumption

The apse

On the exterior of the east end of the church an old Roman tombstone was located, something habitual in the churches of the area (as Ocáriz or San Román de San Millán) and that serves as a distant witness about the intense Romanization of this region.

Inside the temple

Once inside, the church is arranged in two naves, the one on the right being noticeably narrower than the main nave. The transverse arches are supported on corbels, while they rest on pilasters on the north wall. It is hard to specify, in the absence of archaeological studies, if the naves date from the same period or if, on the contrary, the attached nave dates from a later stage. The baptistery was originally located in the side nave, decorated with the baroque sculptures of Saint Peter and Saint Paul that are today semiabandoned at the feet of the temple.

The altarpiece of the side nave, dated from the late 17th century and dedicated to the Lady of the Assumption, was initially located in the east end of the church, hiding part of the paintings.

The red paintings

Before commenting on the paintings of the church, it is important to distinguish at least two well-defined stages. From the impost that runs through the apse and the presbytery upwards are the original paintings, the oldest of them all. From this line down (impost included), the second pictorial stage is developed, which, due to the characteristics that we will mention, could be dated between the 14th and 15th centuries. The entire temple was redecorated during this same period, since many remains of simple fragments in red iron oxide and vegetal rinceaux can be seen across the perimeter of the south large window.

First stage (12th century)

From the very moment of its appearance, diverse theories emerged in very varied directions. One of the most repeated ones is the one that sets its chronology within the 14th century that, besides, links its representation to the Battle of Nájera, a battle fought in 1367 that brought King Peter I of Castile face to face with his half-brother Henry of Trastámara, who aspired to the Castilian throne. In this battle, Peter I asked the Black Prince (Prince of Wales and Duke of Aquitaine) for help, whose powerful armies were in France in the context of the Hundred Years’ War. Those troops passed through the close town of Salvatierra in a well-documented deployment, which has made historians imagine that the paintings had some kind of connection to all this. However, the late date of this battle makes this link unsustainable.

Although the case of Alaitza is exceptional, the truth is that it is framed within a pictorial current that has multiple examples in the province. The churches of the 12th-13th centuries in Álava were originally finished with a plaster of white lime on which some decorations were made in ochre hues or red iron oxides. This decoration can be seen in Legarda, Gopegui, Añua, Arbulo or Obécuri, among many others, this one being the first layer of paint. Therefore, by comparison with these collections, the decoration of the semi-dome of the apse and of the vault of the chancel (where all the figures are) has to be contemporary with the time when the temple was completed.

Compared to buildings of similar characteristics preserved in the area and of which we have approximate datings, we can affirm that good part of the paintings of the church were carried out in the 12th century. Therefore, it is not coherent to think that the church was completed in the specified dates and that, almost 200 years later, when the Battle of Nájera was fought, the motifs that today cover the vaults were painted. In addition, we can see that the armament that the soldiers carry is not that of the Black Prince’s army, but it rather fits with the chronology of the 12th century.

Pictorial sequence

We will comment on the pictorial sequence next. It is only a suggestion, as the paintings accept numerous reads in different orders.

Compositional scheme of the apsidal basin

Siege of the castle. It is a castle built on a hill with scaffolds and wooden corridors around. Some characters defend it with spears, crossbows and throwing liquids or blocks of stone.

Soldiers and centaur. Above the king, some foot soldiers seem to try to attack the knights. They carry military armament. Among them, a curious centaur appears. Its symbolism has been very controversial (from considering it as a Christological image to an image of evil).

Procession of women. Over the knights to the right, a procession of women (each one carrying a different element) goes to a small temple where two women are inside.

Compositional scheme of the presbytery vault (presbytery side)

Childbirth. On the left, a married woman in a headdress is giving birth to a child whose head is sticking out between her legs. Below we see a bucket, an element used in childbirth.

Procession. A procession of women in mourning who carry a ball (or knob) on their hands approaches a church. All of them wear rich costumes, which alludes to an elevated social class.

Compositional scheme of the presbytery vault (epistle side)

The church seems to have undergone an important renovation probably in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. There is no documentation that supports it, but we can see a change in the pictorial decoration with a more detailed style. The vegetal rinceaux, however, remind us of those that decorate the semi-dome of the apse, so it would not be strange to imagine that, when this new decoration was made, the old was still uncovered and that there was an aim to visually harmonize the whole.

Inscription (XIV-XV centuries)

Below the impost, we see an inscription that also corresponds to this second stage. According to the research of Mollà i Alcañiz, the inscription would date from the mid-15th century, from an antiphon of the Mass of Corpus Christi written by Saint Thomas Aquinas. The translation would be: “The salutary fruit was given by the Lord at the moment of his death so that it was tasted” and “pull it up… for the lord… and naked the Gehenna”. It is a text that, in its first part, alludes to Christ’s death with a redemptive tone. As for the theme (the redemption of the sins and the salvation of humanity motivated by the sacrifice of Christ on the cross), it is not far from what we can see in the iconographic programme of Gazeo.

Photo credits:

Current photographs: © Alava Medieval / Erdi Aroko Araba

Old photographs: Archive of the Historical Territory of Álava